Memories of an Evacuee

Recollections of Wartime

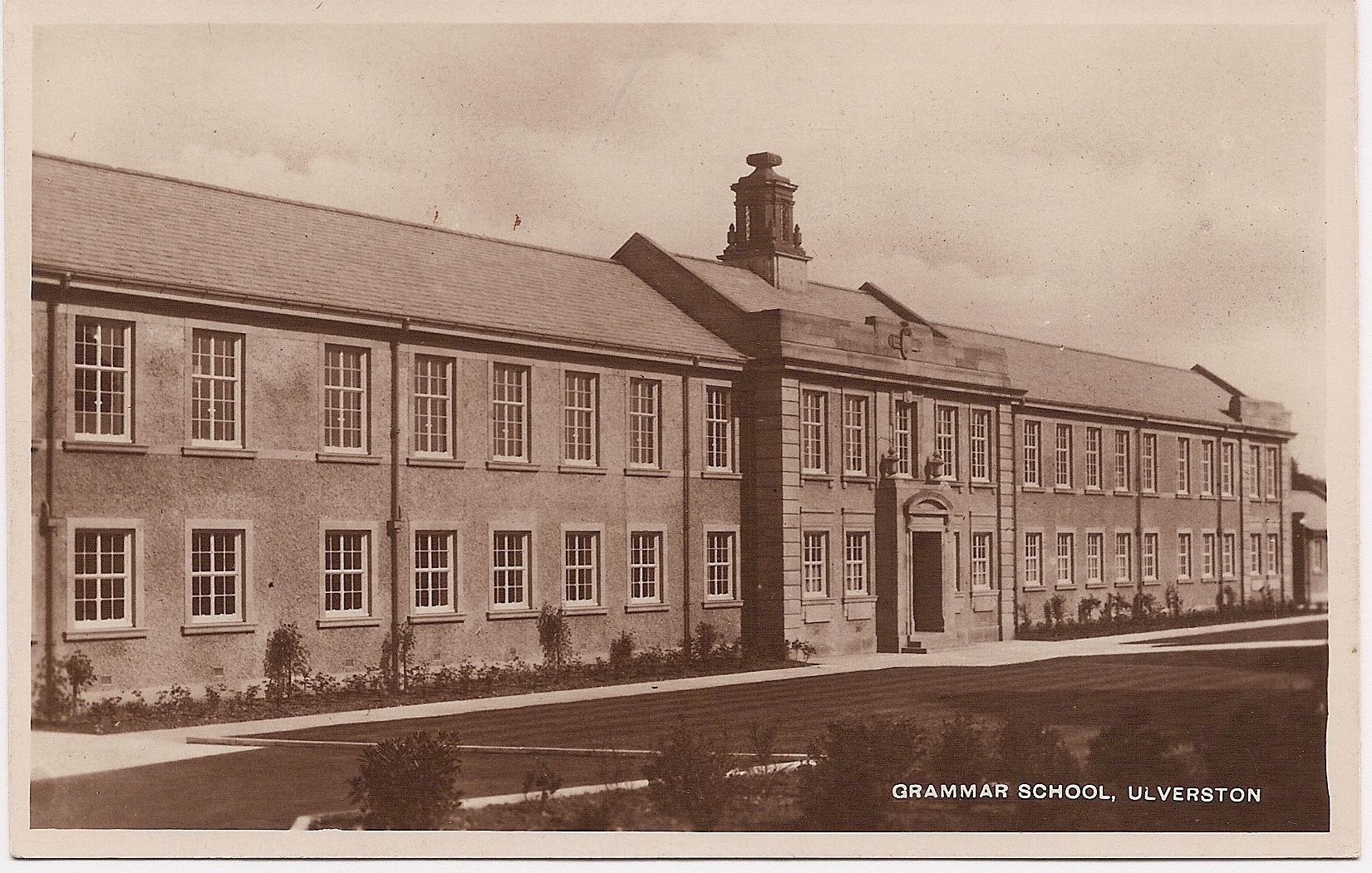

at Ulverston Grammar School

during World War 2

by Mahala Menzies

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, I was at school in my home town of Bristol. We were issued with gas masks, which we had to take to school every day.

That autumn, daytime air raid sirens started to sound off, which meant that our whole school had to pack up our books and descend to the basement cloakrooms with the teachers, to continue lessons sitting on the shoe racks. Nothing ever happened, and the all-clear would usually sound fairly soon after. Needless to say, our studies suffered.

Bombing started nearer to Christmas and our family, living in central Bristol in a very old row of houses (probably built with slave trade money) had to descend to the cellar. My father was abroad, so for the Christmas holidays my mother and I went up to Cumbria where Grandpa Menzies was the doctor in the village of Kirkby-in-Furness, situated on the estuary of the River Duddon and underneath a vast moor and slate quarry, the other side of which lay Ulverston. Dr Menzies lived at ‘Highfield’, the large house that went with the practice. The front lawn was laid out for croquet, at which Grandpa was an expert. He used to play with the postman, known as “Postie”, who was also very good.

Opposite Highfield lived Miss Mary and Miss Millie Harrison. Miss Mary taught at a school in Barrow and was the head of Kirkby Girl Guides. She was a strong-minded lady – you wouldn’t misbehave in her lessons – but she had a sense of humour. Grandpa’s daughter-in-law, Mrs Douglas Menzies, was head of Brownies and very friendly with the Harrisons. When Douglas and Ivan were children, Grandpa and Grandma lived at Little Croft.

While we were there the Germans began to bomb Barrow shipyard and we could see the flashes of the explosions from Grandpa’s bedroom window. They lit up the night sky. It caused me to tremble helplessly and, though I said nothing, my mother noticed.

The upshot was that Grandpa found us somewhere to live in the village and my mother – I rather think with some struggle, though she never said - managed to get me enrolled into Ulverston Grammar School, starting in Form 1B, moving later to the A’s, until getting my School Certificate and leaving five years later.

There were 3 buses a day through Kirkby, Monday to Friday. They started further up the valley at Broughton, where about a dozen pupils got on and sat at the back of the single-decker, keeping fairly quiet. Then it picked up several more including me, as we went along, plus the public. We had to negotiate a very steep hill at Ireleth, and if it snowed heavily the bus couldn’t cope, so we all had to walk home and go sledging up in the fields. Very nice, and no homework.

On ordinary days the bus would go on to Dalton – a very drab place with a great concrete air raid shelter in the middle of the square. It would drop off the passengers and then whizz us back up the other side of the moor to the school gate. At the same time, other kids were bussed in from Grange, Cark-in-Cartmel and other spots.

School started at 9 am with school assembly, taken by Headmaster Mr Longbottom – an imposing figure with smooth black haircut and military moustache and glasses. Also on the platform sat Miss Hobley, Headmistress, just the sort of person you might expect – no frills or airs and graces, simple clothes, simple short haircut, sensible shoes, high moral standards and dignity.

We would have a hymn, accompanied on the piano by Mr Pilkington, the music master, then a prayer, then finally any notices, then dismissal.

Occasionally Mr Longbottom would say, “Now Miss Hobley wants to speak to the girls.” This usually meant a few words about hygiene, as I remember. And some months later a shower was installed in the girls’ changing room, and we all had to strip off after games and take a shower, although not after P.T.

The P.T. and games mistress was Miss Roma Thrift, a very athletic looking person with a no-nonsense attitude and a strong voice. Sometimes, if it was wet, we were allowed to play Pirates in the gym, as opposed to hockey or netball (which I hated), or tennis. Then all the equipment was let down – parallel bars, ropes etc. – and some sort of organised game was played – I think by a couple of girls as pirates chasing the rest of us round the gym, with all of us using the ropes etc. Nobody ever got hurt, and I was one of the few who could climb to the top of a rope.

After the first year when everyone took domestic science (girls – sewing; boys woodwork), we were allowed to take German as an alternative. Most of the girls in our class (now 2A) took German, along with several boys. The teacher must have been Austrian as she spoke with an accent and had difficulty keeping the boys in order, so we didn’t progress very well. I felt sorry for her and sometimes after the lesson wondered if she was really happy. I can’t believe she was, but it was a bit the same for our form-mistress, who took the whole class for History, but she shouted a lot and managed to keep order.

The Latin, Maths and Physics masters were pretty efficient, but our French master was a model and I once came top in French. He took a personal interest in us, one felt, and without effort kept control, although one could tell that if he were angry, one would know it – a stern look would come in his eyes. Alternatively he could teach sitting on the teacher’s table with his open attaché case alongside, and sometimes crack a joke. I remember one about a British Army sergeant ordering food in Paris for the “messe”. But you could tell he loved France.

The Physics lessons, of which there were two double periods a week up in the lab, used to bore me to tears – an utter waste of my time. If only one could have taken another language or something. Once a number of kidney dishes, each with an ox eye in it, appeared on our desks, which we had to dissect !

When the dismissal bell went at 3.50 pm there would be, for a number of pupils, a double-decker outside the school front entrance waiting to take us as far as Dalton. A small group left earlier for some other bus – the teachers always made sure they were given homework. At Dalton we had a dreary fifteen minute wait for the single-decker home.

Very occasionally the little greengrocer on the square would have in a consignment of oranges and we queued up for one each. To pass the time I introduced a tennis ball, which we tossed around all round the square (barely any traffic) for which I was hauled up before Miss Hobley and ticked off. Subsequently I introduced a very lengthy skipping rope in which everybody joined. This too was duly banned, and I was told I must learn to lead people in the right direction.

One consequence of this lack of transport meant that I could not stay after school for extra tennis coaching which I would have loved, nor take part in a school play. I did stay though for a series of Greek dancing lessons (girls only) taken by Miss Thrift the gym mistress. Then I would have to take the train to Barrow and out again on another which went all round the estuary: Askam, Kirkby, Broughton, round under Black Combe to Millom, with its fiery iron foundry. This meant not getting home for “high tea” till about 6.30. Homework had to be crammed in, but not on a night when the Home Service broadcast ‘Monday Night At Eight’, or our favourite, ‘ITMA’. On Saturday evening it would be ‘The Happidrome’.

Other days I would get home at about 5 pm.

On a Thursday my mother would also take the bus to Ulverston. She had joined the W.V.S. and spent the day at the Town Hall sorting parcels from America – mainly clothes, I think. So that evening we would have fried fresh cod steaks for tea with perhaps chips or bread and butter, the fish coming from Ulverston market. That was a treat.

We also had to buy my uniform from Birkett’s in Ulverston which was getting low on stock. I got the blouses, tie, pullover, black stockings and hats, but Mum made me a tunic and summer dresses.

At one point we each bought a pair of wooden-soled shoes (no need for ration coupons). Hers were bright green, mine bright red, which certain of the girls ridiculed. But, “It’s wartime!” and Miss Hobley couldn’t say anything.

During my time in Kirkby there was one shop opposite ‘The Commercial’ pub, run by the formidable Miss Curwen. Her one-armed brother drove a delivery van round the village which stopped at Burlington House, and we would buy Goosnas’ meat pies and cakes.

At the end of the Christmas Term there would be a dance in the hall. Everyone had to take something for tea/supper. These items would be taken down to the dining room to be sorted by the kitchen staff, divided among the cake plates and placed on the tables at tea time. Of course one hoped one would get one’s own sandwiches, and those mixed platters didn’t look too appetising - usually thick sliced bread with a choice largely of meat paste, fish paste, perhaps sardine or (rarely) spam, egg (if one came from a farm) and jam: remember we were tightly rationed. To drink, there was orangeade.

The father of my form-mate and friend, Mary Postlethwaite, who lived just along the road, still was able to run a car, and he would drive over the moor to bring us home, stopping at Ulverston’s “milk bar” (I think we called it) on the square, to drink a hot orangeade. We could not have come home on our own in the dark, going by train to Barrow and on to Kirkby, followed by a twenty minute walk along the lower road, first to my home, Burlington House, owned by the slate quarry, and then on to the row of cottages where Mary lived. Mr and Mrs Geddes – the quarry manager – also lived in part of the Burlington House set-up; also Mr Robinson, who worked in the quarry, his wife, daughter and sister-in-law. I don’t know about him, but he was always in rough working clothes and spent hours in their large garden, which stretched to the road.

Where the road reached the main road between Grizebeck and Kirkby, one could see the old farmhouse up in the field across the road. I think it was medieval. One day I had to go and report that one of their sheep in the field behind our house kept falling over, because it had a disease.

Another time, as I was cycling back from a ride out, I saw a sheep in that same field drop its lamb. As my knowledge of birth was nil, my mother said my face was green when I got home and told her!

A very nice teacher who produced the school plays persuaded me to take part in three showings of ‘The Rose and the Ring’, wearing one of my mother’s outfits which she had made herself for some opera she had been in. (I think it was ‘Die Fledermaus’ with the Carl Rosa opera company.) The teacher was thrilled – worth all the extra train travel and fares! Mum came. I don’t really know what she thought.

We were also visited by a ballet company and a Shakespeare company including Dame Sybil Thorndike, who knew my Ma. Also an actress called Nancy Price gave a reading on stage, I think accompanied by a small dog. The ballet became my great love, but I realised I was not built for it myself.

For a while I took piano lessons at home from organist Mr Raby of Broughton, whose son Ken was also at U.G.S. and at lunch time would tinker about on the hall piano surrounded by his pals (classic items, not pop or swing). Another older boy – perhaps a prefect – was Paul Rimmer, who became a clergyman in Oxford.